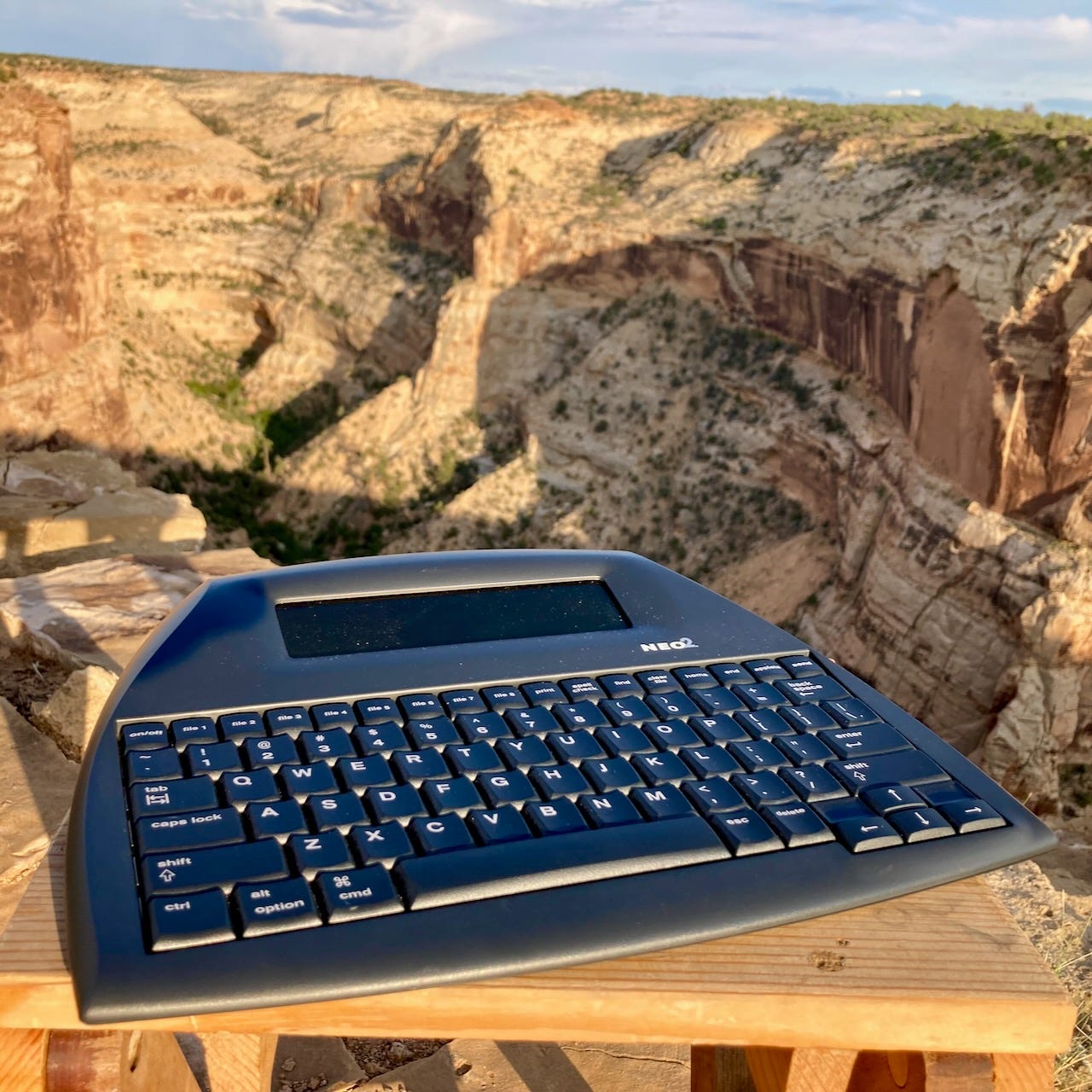

I went out to the Utah desert to think and write about the future of the American republic while I finished Erwin Chemerinsky’s No Democracy Lasts Forever. How the Constitution Threatens the United States. There’s something about the solitude and the stark landscape that facilitates deep reflection on difficult topics. Glimmers of hope can appear in the cracks of the red rock wilderness.

You can tell we’ve reached an inflection point in the 236-year history of our current form of government because people have lost faith in it. According to the Pew Research Center, “Just 16% of the public say they trust the federal government always or most of the time.” Moreover, about 63 percent of Americans have “not too much” or “no confidence” in the future of the U.S. political system. An increasing number of us believe that the American republic is beyond repair. What should we do, assuming we want to avoid a messy resolution to our predicament?

Rewrite the Constitution

I always have my students read and discuss Thomas Jefferson’s letter to James Madison dated December 20, 1787, in which Jefferson comments on the Constitution after having first seen it. Remember that Jefferson was not at the Constitutional Convention but was in Paris while the Constitution was written. I’ve always been struck by this comment Jefferson made in his letter:

“I do not pretend to decide what would be the best method of procuring the establishment of the manifold good things in this constitution, and of getting rid of the bad. Whether by adopting it in hopes of future amendment, or, after it has been duly weighed & canvassed by the people, after seeing the parts they generally dislike, & those they generally approve, to say to them ‘We see now what you wish. Send together your deputies again, let them frame a constitution for you omitting what you have condemned, & establishing the powers you approve…’ At all events I hope you will not be discouraged from other trials, if the present one should fail of its full effect.”

If, at the very beginning of the republic, Thomas Jefferson could argue that we should be willing to rewrite the Constitution to better serve the American people, perhaps we should actually rewrite it. As my post last week made clear, we know from awful experience the problems built into the Constitution. We know its weaknesses, which have unfortunately been exploited to perfection by the conservative movement and those bent on translating wealth into political power.

Under Article V of the Constitution, states can call for a constitutional convention if two-thirds of them agree. Any amendments approved by an Article V convention need to be ratified by three-quarters of the state legislatures. This is a very high bar, and consequently we’ve never convened an Article V convention. For this reason—and also because of the precedent that delegates to an Article V convention would probably be chosen by parochial state legislatures to represent the narrow interests of the states—Chemerinsky suggests that we not follow this procedure.

Instead, Congress could call for a constitutional convention following the precedent of the Philadelphia convention in 1787. Chemerinsky suggests that the President could name delegates equally divided among Democrats and Republicans to attend the constitutional convention. Here is the weakness of his proposal. Do we really think that Donald Trump could be trusted to appoint a balanced slate of delegates to rewrite the Constitution? A constitution written by today’s conservatives would be worse than what we have now. Chemerinsky also thinks that we should skip state ratification of a new constitution and put the document to a simple majority popular vote. That’s a great idea. The founders broke the rules to create the current constitution. Why shouldn’t we to produce a better one?

A new constitution could heal the country and put ordinary people in charge of their own destiny. It could cut the ties between money and electoral politics. It could abolish the undemocratic Senate or replace it with an institution that embraces the principle of one man, one vote. It could enshrine a robust equal protection clause and an affirmative right to vote as truly inalienable. A new constitution could implement measures designed to limit partisanship and restrict the power and terms of Supreme Court justices. How about a constitution where the legislative branch passed bills that could be vetoed by a 60 percent popular vote?

Secession

Chemerinsky doesn’t advocate secession or the breakup of the United States, but he recognizes that “the current gulf between the blue states and the red states is enormous, toxic, and growing.” The second Trump administration appears to be using the power of the federal government to go after blue states and cities on issues like the environment, civil rights, and immigration. Given that blue states generally subsidize red states, one wonders how long blue states will put up paying for a central government to beat up on them. If the American republic cannot pass laws and individual amendments to make itself work better, and if it cannot successfully rewrite its foundational document, then the prospect of a national break-up becomes a real possibility.

The Constitution is silent on the whether states can choose to leave the union and does not explicitly forbid secession. Surely, the founders would have forbidden it if they were so inclined. As Chemerinsky notes, “In the 1850s, when the constitutionality of secession was raised, the federal government initially said that there was no constitutional limit on it,” and that Lincoln calling South Carolina’s secession a “rebellion” and using military force to stop the formation of the Confederate States of America was constitutionally suspect.

We can safely assume that few Americans would welcome a bloody civil war, although the small number of America’s civil war accelerationists should not be underestimated, especially since the second Trump administration appears to be encouraging their development and expansion. Absent another civil war, two main possibilities arise.

The United States could devolve all power to the states except for foreign relations, the military, immigration, the money supply, and foreign trade. The central government would also retain a supreme court, but one focused on adjudicating the balance between the central government and the states. This would leave states to diverge even further on a wide range of issues such as education, civil rights, civil liberties, criminal justice, housing, bodily autonomy, public health, and economic development. Essentially, this would be a middle step between the old Articles of Confederation written in 1777 and the Constitution written in 1787. The Articles tried to centralize certain authorities in a national government but effectively allowed states to pursue their own foreign relations, trade, and monetary policy. The central government was even dependent on states for its military needs and tax revenue. The Constitution, with its enumerated powers, elastic clause, limitations on states in Article 1, Section 10, and the supremacy clause was a real pendulum swing away from a confederal system.

A more carefully delineated federal system could work, but I would not be placing bets on that outcome. The divergence in state public policies and political cultures would also lead to contention in the central government over trade, diplomacy, and military priorities. I suspect that under this model, some of the states would devolve into patrimonial oligarchies while others would flourish as progressive democracies. How do such neighbors effectively work together at the national level?

The second possibility would be a true national divorce, in which each state became its own sovereign country. The United States as a superpower would disappear, the prospect of which drives the neocons crazy because they worry about other entities filling that power vacuum. First question: what would happen to America’s nuclear weapons? All the new sovereign countries would want their share of the former United States’ arsenal. Second question: could Americans set up collaborative entities to manage interdependencies as mundane—but essential—as power generation and distribution, railroads and highways, and air traffic control across national boundaries?

A truly national divorce would be very disruptive. The national legal structure and court system would disappear. As the fifty new nation-states diverged in character, less desirable countries would try to keep their citizens from moving to more desirable countries to access economic opportunities, civil rights, and ownership over one’s own body. Hopefully, the new nation-states would see the benefits of a free trade zone linking them together, but there are no guarantees on that front. Undoubtedly, foreign powers would attempt to pit the new countries against each other.

My friends, we are in a colossal political jam. Our current system is not responsive to the will of ordinary people and keeps reflecting the interests of the already empowered. It shows no signs of self-correction, especially since corporations and the wealthy have hoodwinked millions of Americans into acting against their own interests. The Constitution itself is overly difficult to amend one change at a time. Calling a new constitutional convention is full of peril and could make the situation worse, depending on who gets to write and ratify the document. Secession or devolution, even if they could be effected peacefully, have their own downsides.

We have made significant progressive changes in the past. Think of the 13th, 14th, 15th, and 19th amendments. Think about anti-trust laws, environmental regulations, and civil rights laws. Some of those changes came about peacefully while others only emerged out of bloody battles. Progressive change, even in the context of a dysfunctional system, is possible with concerted action. The lesson I take is that every progressive-minded person has to contribute in their own fashion. Write, if writing is your thing. Run for office, if that fits your personality. Organize, if you have a knack for organizing. Donate, if you have the means. March, every chance you get. Vote, because elections still matter. Join, because all of us can join together.